An Intro to Laws and Morality

Freedom and Law

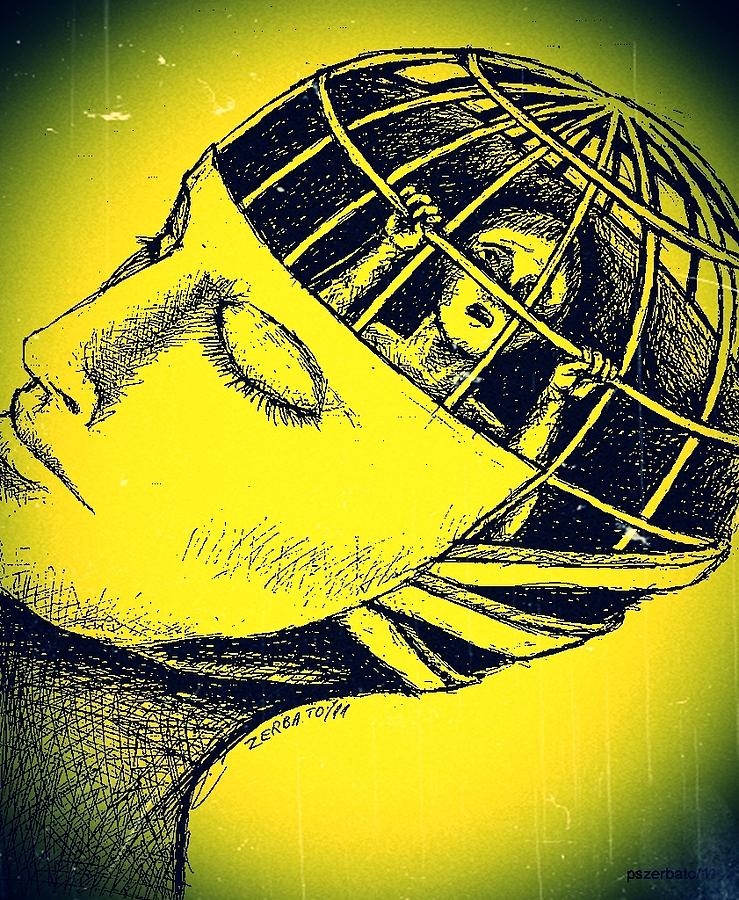

'With laws our freedom is restricted'

This is a very common remark nowadays. But what is ironic is that without laws, there would be no freedom; laws pave the way for our choices, and act as a 'frame' by presenting us with all available options and allowing us to meet our goal. Without law, there would be nothing to choose or love. In moral laws, for example, we can choose to follow them or not, but we would not be able to choose or follow anything if it were not for the existence of the law itself. Likewise, we use traffic lights to signal traffic, and there are traffic laws.

These laws aren't in any way restricting our freedom, but actually enable us to reach our goal without failure (in this case, cross the road without becoming a pancake). Without these laws, it would be impossible to reach aims successfully, and freedom would become redundant.

Thus, morally speaking, there can be no freedom without law, and there would be no need for law if there was not freedom.

Eternal Laws

There are many types of law, but the ones that existed since the beginning were the eternal laws.

An example of a eternal law would be that there is a gravitational force acting on you right now, or that water can boil given it reaches 100 degrees centigrade. Obviously, science describes gravity and changes in states of matter with extreme detail (the how), but it cannot answer why it happens in this way (such as why specifically 100 degrees).

Thus, one is forced to conclude that either a 'higher power' established these laws or they were just there since day 1 (which is another question for another article). Either way, they're called eternal because they are what they are, and they have been since the beginning of time itself.

All eternal laws are obviously universal, immutable (do not change through time) and obligatory.

Moral Laws

A type of eternal law is moral law, which deals with good and evil. Naturally, these only apply to free beings. A rock, for instance, cannot be 'good' or 'bad', and neither can it obey or disobey moral law, whereas a human can, because we are free.

Moral law is eternal because it is universal, immutable and obligatory. Moral law has existed from day 1, although our cluttered nature will often cause us to disregard or disobey it. For example, all humans can agree killing innocent lives is bad, and you don't need to have a special degree to know that. In fact, all you need to do is be human, and these moral laws will arise from there.

Human Laws

This is a type of law that is not universal, is mutable and may or may not be obligatory (dependent on the situation).

Human laws are laws that are used to order our social lives, such as traffic light laws, so people can be free to reach what/where they want to be.

However, human laws that clash with natural, eternal laws are NOT laws. For example, even if a Nazi was ordered by human law to kill an innocent person, he himself would recognise that this law cannot apply to human beings, since there is a greater law (the natural moral law) which overcomes any human law society has set. Thus, all human laws should be in accordance with natural law.

Conscience

The Nazi mentioned in the above example would start doubting the erroneous human law listening to his moral conscience. Each person has a moral conscience, which acts as a self-judgement; judging the actions you've done, you're doing or the ones you're going to do.

Conscience is judgement, as you know the laws and you know your situation, and now you need to decide if the law (whether it is moral, human etc.) applies in your situation and how. This conscience is required because even though eternal laws remain constant, situations change around you, and you must learn to apply the law and how to each one.

By default, a person is obliged to follow their conscience at all times. Doing otherwise would mean you have wronged something/someone. Imagine if I thought eating an apple was a terrible crime and moral wrong (even though it's obviously not), and I was completely convinced of this. If I then started eating apples with full consent, I would think I'm committing a crime and a moral wrong, and obviously I didn't care, since I gave full consent. Now, no one will never know except me, but the evil intention was there, and so I have personally intended and committed a crime and a moral evil. Only the I and the 'higher power' would know.

Similarly, if a person's conscience told them it is wrong to kill but the person then willingly killed a relative, the evil intention and action was there in their eyes, and so they have committed an evil action. Only in this murder case, it was actually wrong, and not just eating apples.

It's important to note that one's conscience can be true or erroneous (hence why a person can actually end up thinking certain things are crimes/evil when they're actually not...like eating apples). This happens because we need to FORM our conscience and build it. We didn't have the same conscience we do now as when we were five, because it developed and formed as we were taught right from wrong. So clearly, parents have a great responsibility in teaching right from wrong to help a child form their conscience, and when we're old enough, we have the obligation to ensure our conscience is not erroneous, otherwise we could hurt ourselves and those around us.

A person's conscience can be wrong out of vincible ignorance (it was not their fault they had that idea) or invincible ignorance (they just don't want to know right from wrong).

As well as true or erroneous, a conscience can be certain or doubtful for particular situations. If you find yourself in a situation where you doubt you know what is truly right, you must clear up your doubts before deciding. If certain, then obviously one should follow their conscience.

The Morality of Human Acts

As mentioned before, morality is about good and evil, and an action can only be good or evil if it is a free action (so if a rock rolls over due to wind, it can't be described as a 'good' or 'evil' action).

Nevertheless, even though we're free, not every action we commit is good or evil. I might just be walking, but walking in itself is not good or evil. In this case, more context is necessary. Going for a walk is different, because it is the proximate end to a deliberate action.

To determine the morality of an action, 3 sources of information are necessary:

- The object of the action: what you're doing, the proximate end to a deliberate action (eg- not walking, but going for a walk)

- The end of the action: the purpose/intention (eg- to help my relative)

- The circumstances of the action

For an act to be good, it needs to have a good object and a good end. If I rob a bank (the object), to give to the poor (the end), the object is bad but the end is good, so the act cannot be good overall. The famous saying 'the means do not justify the ends' summarises this concept.

Also, if the object is good (such as giving a sweet to a friend) if the end is bad (my intention to stop my sibling eating that sweet), then the action is bad overall. This clearly is also the the case if both the object and end is bad.

In conclusion, the object is a means to get achieve an intention (end), but cannot be justified by that end.

The circumstances of the action do not change whether it is good or bad, but they simply determine to which degree they are good or bad. For example, if a person gives money to a charity (good object) to help them out (good end), it is a good action overall, but if that person is rich and it hardly costs them anything, then it is not as good as if a middle class person did the same out of the little money they had in comparison.

Overall, the morality of the action is independent of the circumstances. Killing an innocent person, for example, will always be bad, regardless of circumstances.

Intrinsically evil objects are those that will always be evil (such as killing innocent people, and stealing outside of your human right)

An indirect voluntary is a negative collateral consequence of an action, carried out with indirect will (so the intention wasn't for it to happen, even if you were aware it would). A typical case of indirect voluntary is a pregnant mother who has cancer, and chemotherapy could kill her unborn child, but lack of treatment would kill her. A doctor here can morally treat the mother with chemotherapy, because the doctor's intention is to treat the mother, the intention was not to kill the child, and if there were any way to save them both then that should be the decision taken. Similarly, in the movie 'Eye in the Sky', US intelligence forces see a group of terrorists with obvious intention to suicide bomb a city, but next to the terrorists is a small innocent girl. If the US intelligence forces target the terrorists, the girl would die with the shock wave, but if they didn't target them, thousands would die later in the suicide bombing. Here, the moral thing to do would be to target them, because the intention was not to kill the girl but to kill the terrorists. The girl's death was indirect voluntary, and if there were any way to prevent her death and kill the terrorists that would be the way forward.

Responsibility

A person can be said to be responsible if they know the consequences of their actions. Thus, to be responsible, we must know the truth, which requires us to be free.

Responsibility can be diminished by circumstances. If a person has a panic attack or is half-awake, we do not know to what extent they consented to their actions. If I punch someone while having a panic attack, only I will know to what extent I consented.

Comments

Post a Comment